Unity’s Quiet Betrayal

A red sky in Phoenix at the end of Election Day. Photo taken by Erin Dooley.

I began my day at 6 a.m., anxious yet determined. I had never managed an election site before and didn’t know what to expect, especially in such a charged political environment. My fears about potential intimidation and aggression hung heavily as I prepared to fulfill my role. Several weeks of preparation—training calls and election protection sessions discussing potential unrest—had made me aware of the high stakes. I was stationed in Phoenix at the Osborne School District polling location, where limited parking and rush-hour traffic created frustrating bottlenecks.

The atmosphere on the ground was complex. There were moments of unexpected unity, surprising me amid the polarized tensions. A vocal Trump supporter attempted to intimidate voters, while across from him, a “Trump corner” was adorned with flags and signs. Nearby, a Harris corner with donuts, pizza, and “Republicans for Harris” signs quietly countered the scene. For my current job, I was part of a non-partisan diverse group of interfaith communities, all committed to helping voters find their way. Even a few older white Trump supporters joined in, assisting people in navigating the chaotic setup. Then, as if to signal an unlikely harmony, an African American DJ arrived, filling the air with music that even the Trump supporters couldn’t resist tapping their feet to. In that moment, I was reminded that, despite our differences, we have to coexist, working and raising our children in this shared space we call home.

But what that moment also taught me, post-election, is that much of that “unity” is false. Most of that “togetherness” is a facade—a social display of organized harm, parading with joy over those it brutalizes, what Emilie M. Townes calls a "cultural production of evil." How can those who find entertainment in our culture (food, music, art, inventions, etc.) continue to vote in ways that keep us oppressed while training us to uphold their values as a measure of “winning”—a false American dream of “making it”? This is a dilemma I feel will take me much longer to understand.

Rev. Sekou once said, “One of the myths of the American Empire is that White people are free.” But a system that blatantly opposes the well-being of those on the margins ultimately opposes itself, unable to recognize how interconnected we truly are, no matter how much some want to deny it. My sister often reminds me that white folks in this country have historically subscribed to systems that work against their own self-interest just to keep Black people from gaining access. That’s why healthcare isn’t universal, why housing isn’t affordable, and why college remains out of reach for so many. America has made everything difficult out of a deep-seated fear and hatred of “the other”—even as these very systems fail the people who create them.

And so here we are, unable to accept the possibility of an overqualified Black woman in the presidency, simply because she is Black—and a woman. While I may not agree with all of her views, I know she would not have been a dictator. That is fact. We’ll never know what we could have become or how we could have healed as a country. We’re left with the hard truth of where we are.

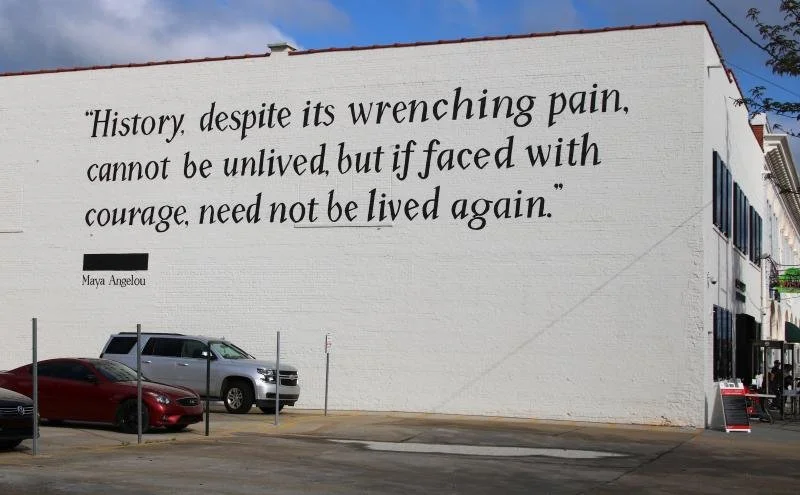

A quote by Maya Angelou on the side of The Legacy Museum (Montgomery, AL)

The unfolding of this election has felt like watching The Hunger Games, where the Capitol’s manipulative control mirrors the sensationalism of today’s elections. Just as the Capitol distracts and entertains, our political process can sometimes focus more on spectacle than on addressing real issues. Power dynamics, much like those between the Capitol and the districts, leave many communities in hardship while others live comfortably, detached from the struggles of the marginalized. Yet the resolve of grassroots movements and voters’ determination to create change speaks to the power of collective action, echoing the unity among the districts.

These reflections also reminded me of my recent seminary studies. We discussed the “theology of conquest” in the Book of Judges, where Israel’s journey to a “promised land” has troubling implications. This narrative of deliverance and conquest has fueled colonial histories, with conquerors justifying their actions as divinely sanctioned. My professor, Dr. McCann’s reminder resonated deeply: the Israelites were never meant to displace others but to coexist. In America, rather than seeking to dominate or marginalize, we must find ways to live and work together in this shared space. This election doesn't just affect us, it affects so many others around the world.

Right now, we’re standing on the soil in Montgomery, AL, here on an all-expenses-paid trip to witness the history of the bus boycott and visit The Legacy Museum. Today is Kendall’s birthday 🎉 (I adore him 🥹), and although we initially had other plans, attending this immersion experience with Arrabon felt like an opportunity we couldn’t pass up. Since we hope to create a similar cultural immersion experience for those interested in learning from the Black story in Durham, gaining insight from people already engaged in this work seems invaluable. This trip to Montgomery feels like a timely reminder of resilience and vision of our ancestors who hoped against all odds and dreamed beyond their reality.

As we prepare to move to Durham and I consider my future, I carry concerns about what this political era means for my safety and freedom as a Black woman. I don’t fully understand what lies ahead, and I fear that no one truly knows what it means to live under a dictator. Few understand what it feels like to watch freedoms slowly slip away. White supremacy is self-destructive, and we’re witnessing that unravel before our eyes.

Reflecting on this moment, I feel the weight of our shared responsibility. Like in The Hunger Games, where the Capitol looms over the districts, our challenge is to build spaces where everyone can flourish, finding unity and strength in each other. This is what Valley and Mountain calls “Zones of Liberation.”

This moment calls me to pay attention—to find communities that care for me, where I can find rest, solace, and safety. It calls me to create these spaces for others and to take things one day at a time. I’m not interested in false hope, but in a hope that builds a more just reality. My commitment to this work requires that I care for myself so that I care for others with longevity.

So today I grieve and sit with the reality that all the people who showed up in protest of George Floyd's murder in 2020…didn't really mean a damn thing.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

How can we navigate the complexities of unity in a polarized society, especially when "togetherness" can sometimes mask systems of oppression and harm?

In what ways can we create spaces of liberation and healing for Black people, where we are not merely surviving but flourishing, despite the systemic forces that seek to undermine our well-being and freedom?