It’s Complicated

Dr. Gould with Rhonda Walker-Thomas and Faith in Florida.

Pastor in the Public Square and Managing Director of Power Building at Faith in Action, the Rev. Dr. Cassandra Gould, is a public theologian, pastor, and organizer with over 30 years of experience integrating biblical justice into activism. As an ordained elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and a national advocate against financial predation, Dr. Gould has been instrumental in bridging the gap between the church and the streets. Her mentorship and coaching helped us birth BLK South, and we are honored to have her on our board. We are honored to have her join the BLK South Board of Advisors. Learn More

In the aftermath of the US presidential election and the glaring political and social realities, as a Black woman in the 92%, I have found myself navigating a multitude of emotions—mine and others. It has been an emotional tango that came with ebbs and flows of feelings: anger, betrayal, grief, numbness, and resolve. A couple of weeks ago, as I emerged from my carefully curated cocoon of family and trusted friends, I realized that Christmas and holiday decorations were everywhere. Normally, I would be angry about the premature capitalistic retail manipulation of consumers and the co-opting of Christmas, but this year I surrendered and decided that maybe it was just what some of us needed. We needed something to celebrate. We need festive lights, holiday food, invitations to dress up, the laughter of children, and we need light—oh, how we need light.

Thanksgiving marks the beginning of that long, windy road into a holiday season that is difficult for many to navigate. If this season had a relationship status, it would be, “It’s complicated.” For some, it is a reminder of the empty chairs, formerly occupied by loved ones who are only present in the spiritual realm. Others, who are alone—whether by choice or fate—often feel lonely during this season. Not to mention the arrogance of Christians as we superimpose our holiday on the masses. Yes, it is complicated. If you are like me, as a person who does more than chant “no justice, no peace” but works diligently so that all may know justice, the origin of the holiday makes celebrating Thanksgiving even more complex. The reality of a celebration that was initiated because of an ill-gotten bounty of the land the Indigenous people owned and occupied, and kidnapped Africans, is never lost on me. Yet, in this season, I need the pause, the intentional village celebrations, and the conjuring of the wisdom and guidance of ancestors.

Angela Hsieh/NPR.

On the Christian Calendar, Advent also starts this weekend. It is a new season, a season of uncertainty and simultaneous expectation. Advent comes from the Latin word adventus, which means "coming." For Christians, this time allows us to have an annual season of preparation to receive the coming Messiah. Politically and socially, it is also a time of uncertainty, and some would say darkness. If we ever needed light, we need it now. There are no political messiahs, and rightfully so, but we have the light that is needed to navigate the darkness.

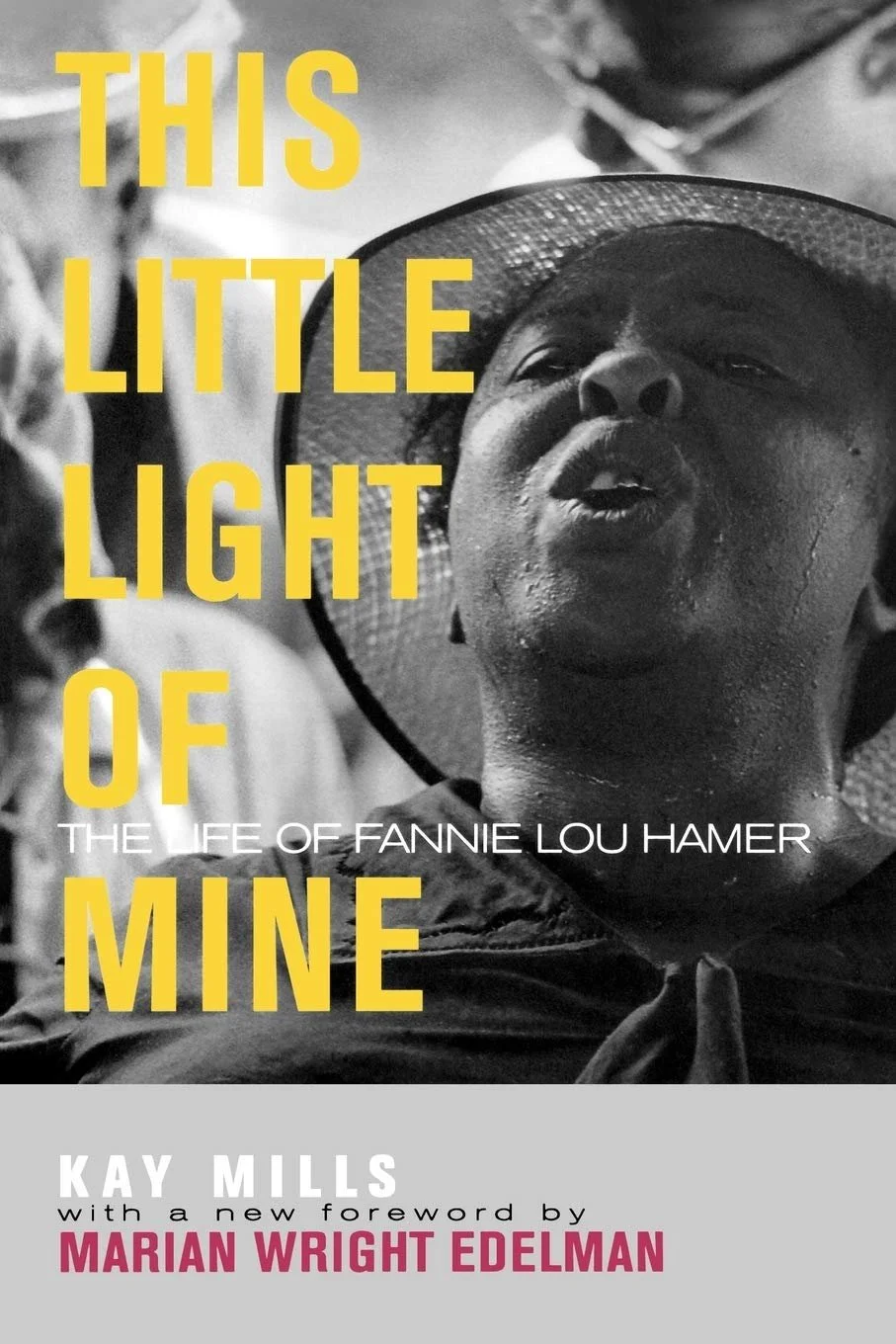

A few weeks ago, I wrote an article encouraging Black people to intentionally engage in what Rev. Dr. Nick Peterson, Assistant Professor of Homiletics and Worship, Assistant Director of the Ph.D. in African American Preaching and Sacred Rhetoric Program, refers to as “Black on Black care” and to draw from the sacred traditions of the Black Church. However we spend the rest of this week and season, I want us to be reminded of the wisdom of the song often sung in Black Church settings of yesterday, “This Little Light of Mine,” a gospel song that could be heard during the civil rights movement, written by Harry Dixon Loes around 1920 as a children's song.

“This little light of mine,

I am going to let it shine, let it shine,

let it shine, let it shine.

Everywhere I go I am going to let it shine.”

This song, and multiple other spiritual technologies from the Black Church tradition, are examples of the rhetoric of protest. As an act of gratitude to the Creator and the ancestors, and to protest the empire, “Let your light shine” in the darkness to remind the world you are still here. You may want to be circumspect and discern where your light is safe, but “let it shine, let it shine.”

Reflection Questions:

How can the holiday season serve as both a time of personal celebration and a space for acknowledging historical and social complexities, particularly for marginalized communities?

In what ways can "letting your light shine" serve as both an act of personal empowerment and a form of resistance against systemic injustice, especially within the context of Black Church traditions?

RECOMMENDED READING