Redefining Greatness Through Black Well-Being

A stronger, more vibrant Black community is an integral component of a more prosperous America. For anyone who has had the opportunity to witness the evolving dynamics of American society, there's a resounding call from the conservative right to "Make America Great Again." However, I firmly contend that for America to truly embody greatness, it must prioritize the well-being of its most vulnerable citizens rather than catering to the interests of the wealthy and powerful.

So, who exactly are the most vulnerable among us in America? They encompass a diverse array of individuals facing systemic disparities, often stemming from racial, economic, and social injustices. If we, as a nation, can make collaborative efforts to ensure that America becomes a place where these marginalized communities thrive, then it will inevitably result in a better America for all its citizens. Embracing inclusivity, equity, and justice for the most vulnerable members of our society will pave the way for a brighter and more harmonious future that benefits the entire nation.

Here are several compelling facts that underscore the historical disparities experienced by the Black community in comparison to the White race in America:

Black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women. Out of every 100,000 live birthday, 42 Black women die of pregnancy-related causes, more than three times the rate for White women.

Black households are two and half times more likely to experience food insecurity than White households. Out of every 100 Black households, 21 sometimes have difficulty providing enough food.

Less than a third of Black students attain a bachelor's degree or higher, compared to almost half of white students. The 16 percentage point gap between Black and white sutdents who have bachelor's degrees has remained steady for two decades.

Black undergraduate students owe about $7,000 more in student loans on average than their white peers after graduation. More Black students need student loans for college than white students, and this taking them graduate with over $&,000 more in debt, on average.

Black adults are more than 1.5 times less likely to have health insurance than white adults. The Affordable Care Act helped narrow the gape between Black and white people, but the disparity has grown slightly since 2016.

On average, Black male offenders received federal sentences almost 20% longer than white male offenders for the same crime. A Sentencing Commission report examining the difference in federal court sentences found that, between 2007 and 2016, sentence for Black male offenders were an average of almost 20% longer than those for White male offenders accused of the same crime.

In 2016, 1 of every 13 Black people lost their right to vote due to a felony conviction, compared to 1 in every 56 non-Black voters. In 2016, more than 7% of the voting age Black population in America was disenfranchised compared to 1.8% of the non-Black population.

Black families have one-tenth of the median net worth that White families have. Black American have one tenth of the net worth of White Americans. Nearly one in five Black households has zero or negative net worth, compared to nearly one in ten White households.

A Black family is about half as likely to own their home as a White family. The large gap in Black and White home ownership has persisted for decades but since the Great Recession in 2008 the gap has grown.

Black households nearing retirement have a median savings of $30,000, which amounts to one-quarter of the amount held by white households. Black households near retirement age (55-64) had just a fourth of the savings held by White families for retirement in 2010.

Black men have a life expectancy of 72.2 years, more than four years less than White men at 76.6 years. The life expectancy gap between Black and white people has narrowed over a century but remains at four years. Chronic diseases, such as heart conditions or cancer, strike Black people at higher rates than White people.

These statistics compel us to introspect and question the root of the issue: how did we arrive at this point? The answer lies within our collective Western worldview, which shows up in our daily choices and decision-making processes. It is our collective perspective, shaped by our beliefs, values, and experiences, that has led us to the current situation. Our worldview influences the way we perceive and respond to the world around us, and understanding its role is crucial in addressing the challenges we face.

UNRAVELING OUR WORLDVIEW

The Western worldview traces its origins back to British settlers who arrived under the influence of the theological principles inherited from the Doctrine of Discovery.

The Doctrine of Discovery is a historical legal concept that originated in the 15th century and was later codified into international law. It justified the colonization and domination of indigenous lands and peoples by European nations. The doctrine essentially asserted that European explorers had the right to claim lands they "discovered," even if those lands were already inhabited by indigenous communities. It provided a legal framework for the dispossession of indigenous lands and the subjugation of native populations, resulting in centuries of injustice and oppression. Today, the Doctrine of Discovery is widely criticized as a symbol of colonialism and is recognized as a violation of indigenous rights and international law.

The Doctrine of Discovery unfortunately led colonizers to adopt a religious belief system that portrayed them as superior to others and justified their actions of taking, stealing, killing, and destroying anything or anyone different from them. This religious perspective was the birthplace of Christian faith in American and has inflicted centuries of harm on Black and Brown communities, evolving into centuries of genocide, land theft, forced labor, and attempts to erase the true history.

A fundamental tenet of Christianity is the equality of all in the eyes of God, yet it was manipulated to reconcile with actions such as land theft and enslavement. The idea that indigenous people were not fully human was used to justify the theft of their lands and the brutal treatment of their populations.

Justice John Catron

One account of how these ideas played out in history is exemplified by a quote from Justice Catron in Tennessee in 1833 during the State vs. Foremen case, where he stated, "It was more just that the country should be peopled by Europeans, than continue the haunts of savage beasts, and of men yet more fierce and savage." To him, Indigenous people were seen as "mere wandering tribes of savages" who "deserve to be exterminated as savage and pernicious beasts." This quote underscores the dehumanization of indigenous populations, allowing the assertion of dominance by whites through the right of power, rather than morality or justice.

It is as if Justice Catron forgot his own history -- with a lineage of German immigrants, he contributed to the oppression of Indigenous people, failing to unlearn the ways of oppression despite his own ancestors migrating West to seek freedom from wars, economic hardships, and religious insecurity.

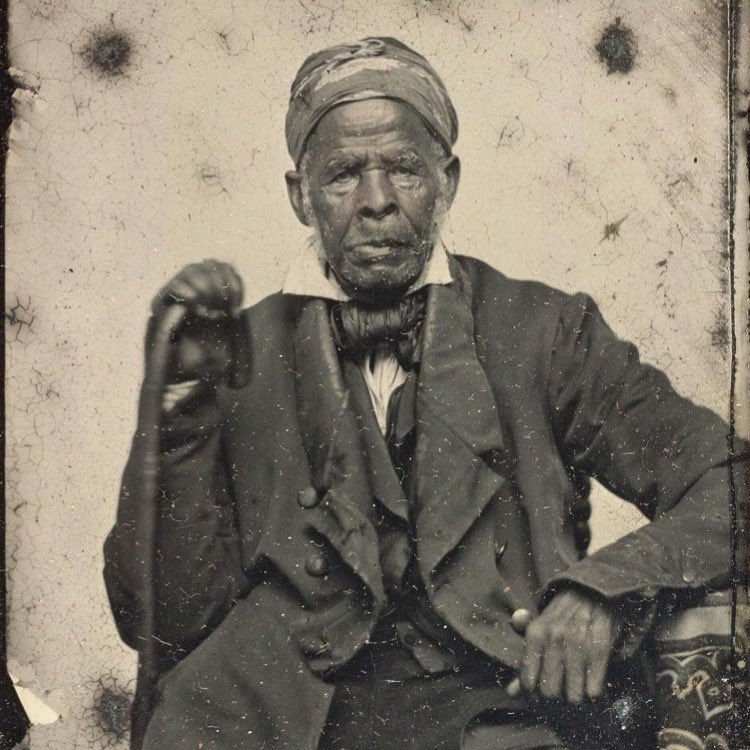

Omar ibn Said

In contrast, the story of Omar ibn Said, a Muslim scholar, illustrates another facet of this history. Stolen from Senegal and enslaved in America in 1807, he left behind an autobiography written in Arabic. His story highlights the violence of the slave trade and the terrors of the middle passage, as he described being captured by "a large army who killed many men" and crossing "the great sea" for a month and a half. Despite being among the approximately one-third of American slaves who were Muslim, the erasure of black Muslim identity among enslaved people aimed to strip them of their identities and reduce them to chattel both legally and in the public imagination. Omar's journey is a testament to the resilience and cultural richness of enslaved African people, despite the dehumanizing forces they faced.

As Americans, we've inherited a fractured and detrimental Western worldview, one that has been a source of considerable global suffering. To rectify these past injustices, it is imperative that we wholeheartedly embrace a fresh perspective founded on the rich histories, profound teachings, enduring practices, profound beliefs, and cherished values of both the Indigenous peoples of Western territories and the ancestral traditions of West Africa. By doing so, we can pave the way for a more inclusive and harmonious future, fostering healing and understanding in our society.

To become “Indigenous” is not to become Indian but to return to our roots and embrace a worldview that has a more communal way of living where all communities can flourish. If we are honest, the Western worldview has broken the Black community it is only the Indigenous worldview that will get us out.

Indigenous theologian, Dr. Randy Woodley, explains that becoming "Indigenous" doesn't mean becoming Indian; it means reconnecting with our ancestral roots and embracing a worldview that emphasizes communal living where all communities can flourish. It is also imperative that we remember that the Black community is also an indigenous community: a people group who existed and were native to a particular place before the arrival of colonizers.

As Hari Ziyad points out, "This is not to say that the experiences of populations indigenous to Africa are identical to the experiences of populations indigenous to the Americas. But it is to say that Africans, including those of us born of the diaspora, are an Indigenous population withstanding the same global colonization efforts enacted by white supremacy that has bled its way—quite literally—across the Atlantic, and our lived experiences as colonized and displaced Indigenous people should be recognized accordingly."

It is quite clear that White Supremacy and the Western worldview have fractured the Black community but, I believe, our ability to once again become indigenous and return to our ancestral communal practices, creates a route to restoration.

RELATED:

INDIGENOUS IDENTITY REVISITED:

BLACK COMMUNITY'S REVERSE MIGRATION

The differences between the Western and Indigenous worldviews are profound and offer contrasting perspectives on how individuals and societies relate to the world around them. In the Indigenous worldview, the emphasis is on communal well-being, where the health of the entire community depends on the welfare of the most vulnerable members. This perspective is rooted in the belief that everything and everyone is intricately interconnected, and it is reinforced by laws, kinship systems, and spirituality. Identity in the Indigenous worldview is defined by these connections, emphasizing the importance of relatedness.

In contrast, the Western worldview tends to compartmentalize society, with an increasing focus on individualism. Personal gain and the accumulation of wealth are often prioritized in the Western perspective, which can lead to a sense of detachment from the broader community. In this context, amassing wealth is seen as a means to individual prosperity rather than a collective good.

The idea of reverse migration invites us to return to our roots and reacquaint ourselves with Indigeneity, emphasizing interconnectedness, community well-being, and a more holistic perspective. This shift in perspective encourages us to learn from our ancestors and integrate their wisdom into our modern lives, potentially leading to a more harmonious coexistence with the environment and each other. It calls for a reevaluation of our values and priorities, challenging the prevailing Western mindset in favor of a more Indigenous approach, where the health and happiness of the entire community take precedence over individual wealth and self-interest.

We want to invite you to join us in addressing historical injustices and participate in the nurturing of thriving Black communities. As Indigenous wisdom reminds us, the health of America is tied to the well-being of its most vulnerable members – Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC). In Durham, NC, we want to contribute to the ongoing meaningful work in the Black community and learn from the rich tapestry of history, voices, and identities that have shaped this community. Partner with us as we build a world that aligns with our Creator's original intent – a community of flourishing creation!

SOURCES AND CREDITS: